Prostitution in 1868 New York

Making Ends Meet

Prostitution was a vast industry in 1868 New York, though it didn’t leave a lot of records for us to learn about it. All sex, and most certainly women having sex for money, was cloaked in shame. Prostitution could be a lifeline for women who no other options after rape or seduction. The number of urban women who took this step at some point in their lives in the mid-19th century was around 30%! In the present day when women have access to many more kinds of employment, estimates are closer to 1-2%.

No one counted the percentage of men patronizing prostitutes in the 19th century , but given that 30% of women engaged in the trade, scholars estimate the number at 50% or higher. Paying for sex was an ordinary transaction in New York, where a new class of single men had come to the city to work as clerks in emerging office-based enterprises. Poor working men and rich men found also price points for sex to suit them, and the patrons of prostitutes at every level were indulgently known as sporting men, if their patronage was acknowledged at all.

Respectable women could live their entire lives blind to this vast business. Newspapers rarely covered it. Some social reformers addressed it, but not until the Gilded Age gave way to the Progressive Era in the 1890s did it become a widely debated policy issue, focusing on public morals rather than economic necessity.

Hell’s Hundred Acres, Satan’s Circus, and the Tenderloin

Full-time prostitution in 19th century New York took many forms. Streetwalkers or women renting rooms in assignation houses lived on the edge of poverty and violence. Several grades of brothel, from dirt cheap to very expensive, filled distinct neighborhoods. In 1868 there were well over 500 brothels in the city.

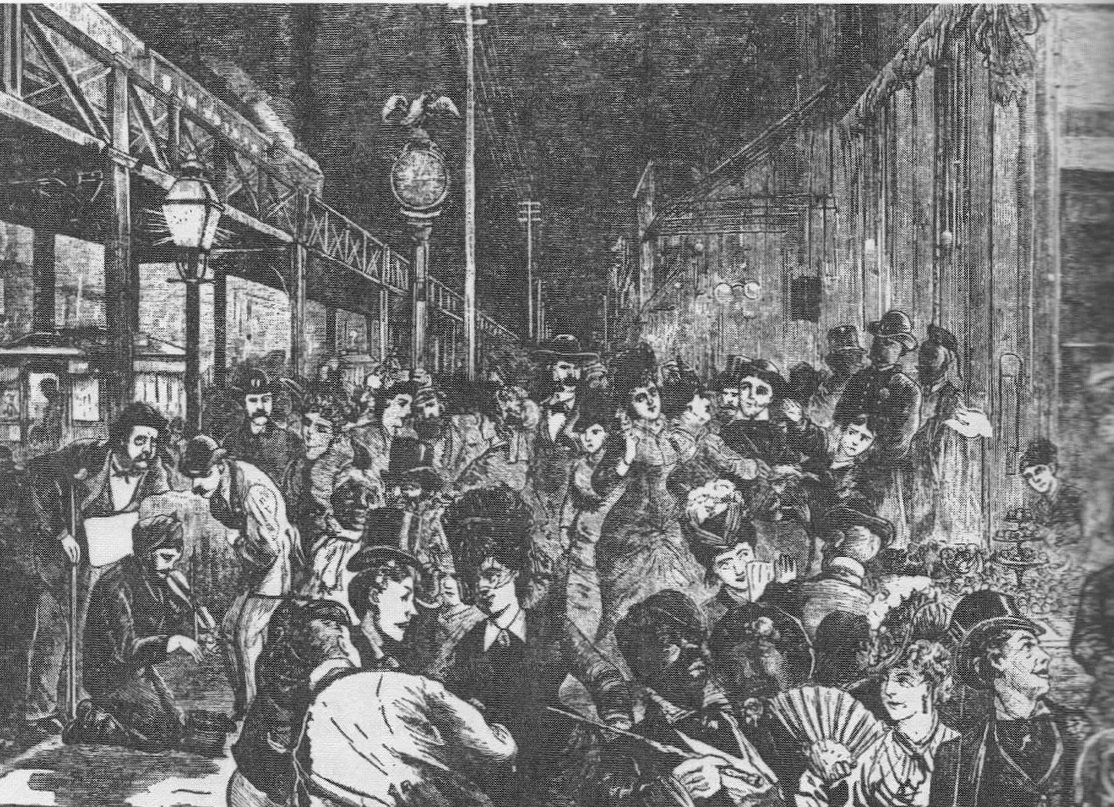

The first vice district was in present-day SoHo, west of Broadway between Houston and Canal Streets, called “Hell’s Hundred Acres” for overlapping reasons. Fires were particularly tough to control in its cast-iron warehouse buildings. Broadway itself was a promenade where harlots met customers even amidst bustling daytime commerce, and side streets counted more than 65 brothels. The Gentlemen’s Guide called Greene Street with 23 houses “a complete sink of iniquity.”

During and after the Civil War, the elite trade followed the theaters uptown, to brownstones in the blocks west of Fifth Avenue between 20th and 27th Streets. That neighborhood, where I sited the Double Standard, was called Satan’s Circus, where half the buildings hosted sexual enterprises. In the following decades, the vice district crept northward along the west side toward 42nd Street, and was renamed by a policeman relishing his prospects for kickbacks when transferred there, as the Tenderloin.

Sporting Men, the Flash Press, and Sporting Houses

A ‘sporting man’ or ‘sport’ in 19th century England and the US was a man who enjoyed gambling, drinking, and keeping mistresses or frequenting prostitutes. The term goes back to the 17th century, but the phrase ‘sporting house’ emerged in the mid-19th century to denote establishments that catered to gamblers, and then became a euphemism for brothels.

A set of newspapers collectively called the “Flash Press” catered to these men, and championed heterosexual male indulgence. Their sexual passion and pleasure were celebrated as be natural and inevitable; its repression pointless and hypocritical. Few of these papers survive, buut a trove was discovered in New Hampshire in 1985 and purchased by the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Massachusetts. Titles recovered included The Libertine and The Weekly Rake. Other prominent papers were called The Whip, The Flash, and The Clipper.

Theeir writers were cheeky—mocking and irreverent—but their take on prostitution was wildly inconsistent. A paper might profile a prominent, elegant madam or celebrate a brothel ball she threw, but in another issue disdain her house as evidence of corruption and undue aristocratic privilege. Sexual liberty was fine for white working men, but not blacks, Jews, or homosexuals. The papers celebrated prostitutes “as necessary as bread and water,” and also moralized like churchy reformers about their depravity, criminal lust, and the abyss of shame, echoing the prevailing virgin-vamp dichotomy. Sporting men wanted to straddle the respectability divide.

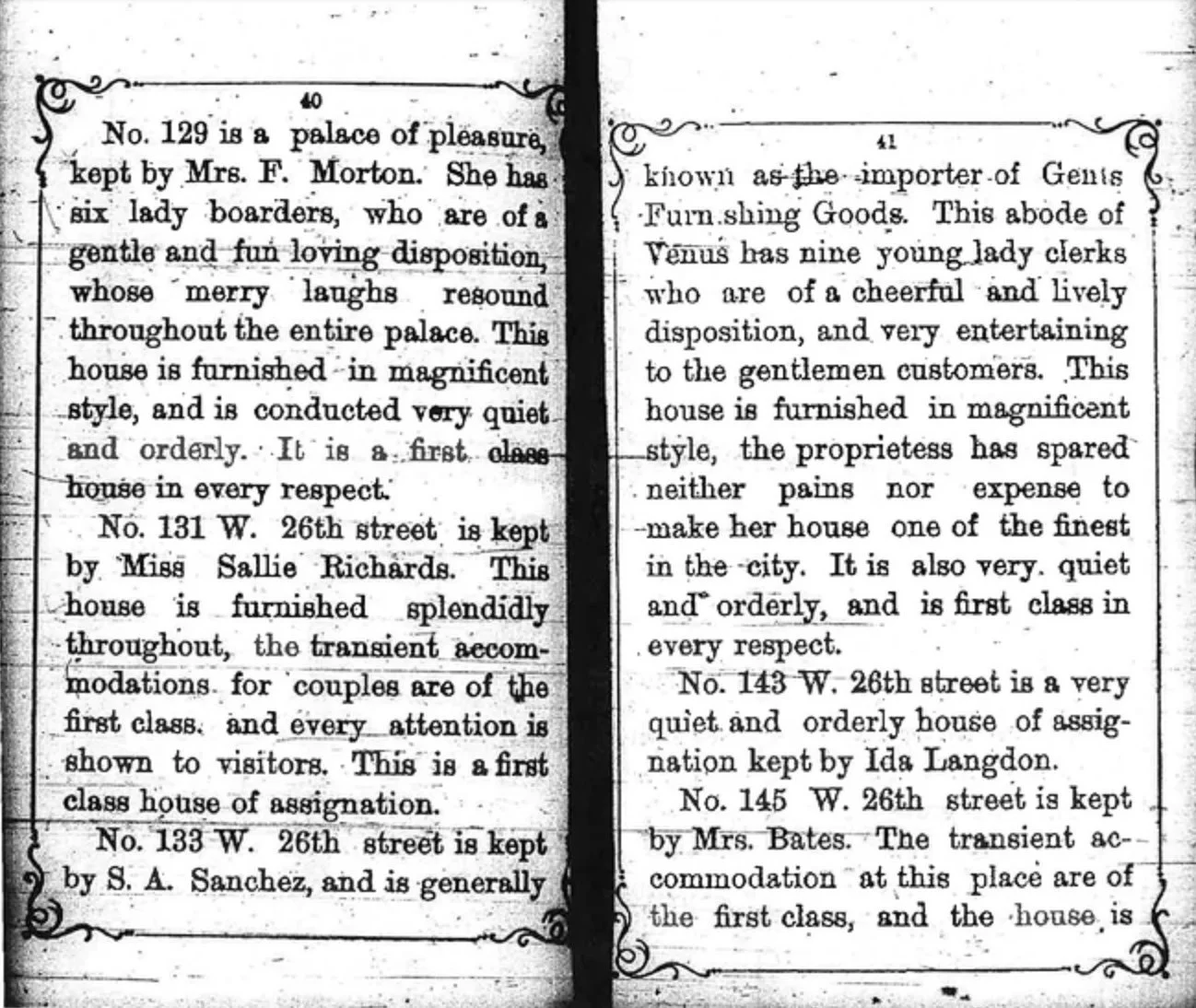

Any number of guides to the brothels of New York were published each year, detailing the names and specialties of particular harlots. The Gentlemen’s Directory, published in 1870, was a pocket guide to the Satan’s Circus vice district, listing 49 houses eight square blocks between 23rd and 27th Streets. Kate Woods’ brothel, known as the Hotel de Wood, boasted expensive oil paintings and rosewood furniture, and she kept three young ladies of “rare personal attractions,” popular with foreign tourists.

Pages from the Gentleman’s Guide to New York, 1870.